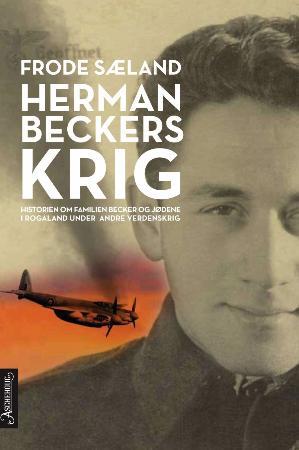

This is a micro history within a

general history. A tale of a Norwegian naval aviator and his efforts in the

Second World War. A story of a named warrior, who rendered faithful service in

the war. Nevertheless, he was cut off from the fruits of victory. This is the

story of Herman Hirsch Becker.

Family background

Herman was born in a village south

of Stavanger on the south-west coast of Norway. His parents were Russian Jews, fleeing

from Russia at the start of the First Word War. His father, Hille, crossed the

Baltic Sea at the age of 29, travelling via Sweden to Oslo in August 1914. In

Russia, his 26 years old fiancé Judith Davidova Zemechmann had to wait for five

months in order to join him. She had visited several European cities as a piano

teacher, accompanying well off families from St. Petersburg on their educational

journeys. She arrived at Oslo directly from St. Petersburg in January 1915.They

married and rented a small flat down town. Hille worked in a watchmaker shop,

while Judith stayed at home, as most women in immigrant families did. In May,

Judith gave birth to her first-born son Israel Josef. The family did not settle

in Oslo, as conditions were bleak. In August 1916, the family moved to the

industrial town of Stavanger, hoping for better opportunities in a town where

the canning industry was booming due to wartime conditions.

The

Becker family was part of a major emigration from the Pale of Settlement in the

years between 1880 and 1920. Nearly 3 million Jews emigrated from Eastern

Europe due to restriction of opportunities, increasing poverty, systematic

discrimination and brutal harassment. The Becker’s escaped as Russia launched punitive

measures against the Jewish population in the western parts of the empire after

the attack by Imperial Germany. Tsarist Russia considered Jews in these areas

to be pro-German. However, unlike the majority emigrating to North America, Europe

and Palestine, a small minority settled in the peaceful corner of Scandinavia,

a region with a historically low part of Jews in the population. By 1920,

approximately 1.200 Jewish immigrants had come to Norway, primarily from

Lithuania, Latvia, Poland, and Russia. They mainly settled in the two towns with Jewish communities, Oslo and

Trondheim, but gradually some moved to other towns and rural regions as well.

Childhood and youth

The family of three moved to the village

of Bryne on the regional railway line in 1918. In four years, the family

counted five. Herman Hirsch Becker was born on July 30, 1920. Their only

daughter Ada Abigael Becker was born in Stavanger on January 20, 1922. At Bryne,

Herman enjoyed a good and safe upbringing. Hille ran a small watchmaker shop on

the main street, struggling to make ends meet. Judith sold candy in the shop in

order to add to the income. She took on pupils learning to play the piano. She

also played the piano at the local cinema screening silent movies of the day

and provided live music at gatherings and celebrations at the regional college.

The

Becker’s may have had limited social intercourse and a modest income,

nevertheless, they were accepted and respected in the small community. Herman

was a lively, talkative boy, making a lot of fun. He was allowed the keep his

full, dark hair rather uncut, in a bohemian way, until he entered primary

school in 1929. Considered an ordinary and proper schoolboy, he did not

distinguish himself in any way. His musical talent, however, flourished as his

father taught him to play the violin.

In

1928, the family moved back to Stavanger. Hille established a watchmaker shop near

the harbour, eventually renting a flat in a respectable part of town. Herman

finished primary school in 1934 with top marks. His socialization into

Norwegian customs and habits happened in a normal, self-evident way. The family

ethos was to become good Norwegians. Like his brother and sister, Herman spent years

in the Christian based Scout Movement. He was like any other boy in the street

- active in play, outdoor activities and competitions. Of course, he learned to

ski, becoming a competent skier. He liked to play football and was a prominent

member of the local junior team. Herman, however, had temperament. He did not

tolerate derogatory remarks on Jews or Jewishness. Whenever someone made a

stupid remark or a joke at his expense, he sat the limit with his bare fists.

In his teens, football and sports gave way for more artistic and intellectual interests. He took regular lessons on the violin and played chess. Although Herman occasionally played the violin for his friends on outdoor gatherings, he was alone in his musical education. Friends regarded him as a quiet and pensive person. New interests, however, were not traded in good achievements at secondary school, where he performed mediocre. I suppose the age of puberty was difficult also with regard to identity. Classical music became his main field of interest, but not exclusively. He was stand-in for the town orchestra, played regularly in the orchestra of the local theatre and listened passionately to American big-band jazz music. His formidable performance on solo violin at a school-ending event in 1937, made a deep impression on many present.

Herman

finished his education with a two-year course at the commercial gymnasium of

Stavanger, graduating in 1939 with good results. He obviously enjoyed the combination

theoretical and practical subjects, preparing him for a job in trade and

commerce. He was well liked and friendly, a cheerful and jovial fellow, with a

friendly smile and a quick reply, usually in the centre of any group of

youngsters, without being a leader type. He was not pious or interested in

religion, although he received a basic religious education at home. Whether it

was related to his elder brother Israel marrying Ida Goldman, sister’s daughter

of the well-known factory owner and tradesman Moritz Rabinowitz, whether it was

related to an improved financial situation for the Becker’s, making a

relatively expensive membership affordable, or whether it was related to the

international situation and increasing anti-Semitic pressure in Norway, we shall

never know. Nevertheless, in September 1939 Mr. Becker applied for membership

in The Mosaic Religious Community, Oslo for the rest of the family.

Herman starting

working in his father’s shop, keeping the books and attending the shop, as his

father grew ill of asthma. He started to earn his own money and perhaps he planned

a career. In November, he reported relocation to Oslo, but he did not move. He

stayed in his hometown, loyal to his family, working as a shop attendant. With

a war on in Europe, times were marred with uncertainty and worry. Many of the

immigrant families of the second wave had relatives in Central and Eastern

Europe. The situation for the 500 Jewish refugees arriving in Norway until 1940

was more precarious, as they had no permanent resident permits.

Herman

was representative for the second generation of Jewish immigrants in Norway. He

spoke the native language, as the families were eager to become Norwegians as

quickly as possible. Most families adopted a particular strategy of adjustment,

a form of self-adjustment, while resisting a strong pressure for assimilation. Families

were largely integrated in society, adopting a Norwegian identity as well as

maintaining their Jewish identity, within a position as a religious minority. Children

of the families received what their parents did not get: social security,

education and a good upbringing, forming a basis for social mobility. An

entrenched, bureaucratic anti-Semitism was probably more of a problem for the

immigrant families than bursts of a latent anti-Semitism in society as a whole.

The authorities demanded 20 years of residence before granting citizenship,

especially to Jews from Eastern Europe. The Becker family received their

Norwegian citizenship in 1936. Many poor Jewish immigrants, however, did not. Both

generations seem to have appreciated the protection given by a hard-earned

citizenship, becoming most loyal citizens.

Grown-up under Nazi occupation

The Nazi attack on Norway on April

9, 1940 came as a shock, to both officials and the people at large. German

air-landing troops quickly occupied the airport, harbour and town of Stavanger,

while Norwegian Army units established defence lines further inland. Neither

Herman nor Ada were part of the panic evacuation by ships to hamlets at the

inner fjords the next day. In town, ordinary life carried on under the parole

“calm and order”. The town was of strategic importance and the Royal Air Force

was on the wings several times. During a bombing raid, two aircrafts were hit

by flak. One burning bomber crashed

in the centre of town, causing a fire at the school attended by Israel, Herman

and Ada. Due to requisitions by Wehrmacht, the Becker’s had to move to a

new flat. The anti-Jewish policy of the occupation authorities became manifest

as local police was ordered to confiscate radios owned by Jews.

In

the early summer of 1940, Herman met a young girl named Aslaug, five years his

junior. They enjoyed each other’s company and soon fell in love. Herman’s

mother did not approve of his choice. As culturally conservative, she insisted

on finding a Jewish girl, to no avail. There were no suitable candidates for

miles – Herman had found his girl. He insisted on deciding the issue himself –

staying out by a rock, the whole night to mark his will adamantly. Reluctantly,

Judith accepted Aslaug, involving her in cooking. Herman and Aslaug became a

couple, meeting twice a week, staying with friends during week-ends and

holidays, doing what young people used to do; go dancing, to the cinema,

hiking, go bathing, visits at family cottage, skiing in the mountains, and

arranging private dancing as public dancing was banned by the occupation authorities.

Aslaug and Herman, summer 1941. Photo courtesy Frode Sæland

It

is impossible to say how occupation affected the prospects of live for young

people. On the outside, seemingly not. However, indications suggest that a

major choice was under way. Herman was a man of integrity, displaying a strong

sense of justice, valuing social equality and believing in national

sovereignty. Parading German troops in his beloved hometown must have been a

provoking and disheartening experience. It can be humiliating for a young man

liable to military service to live in an occupied country. I can imagine his

response to the bombastic music of a military band playing in the town square: although

music seldom was completely free, freedom was an integral part of a nation.

In October 1940, the eldest son of the neighbour family Gilje suddenly left for Oslo. In fact, he crossed the border to Sweden and later joined the Royal Norwegian Air Force in Britain. He and Herman were of the same age, attending a session for compulsory military service half a year earlier. Appeals to report for duty by the government in exile may have reached the young men. The youngest of the Gilje brothers collected petrol for a crossing of the North Sea.

One

summer evening in 1940, while saying goodnight to Aslaug, Herman got agitated

after an air battle over Stavanger. He declared his intention to participate in

similar action as well. To the protests of Aslaug, not wanting him to leave her

for war service, he muttered equivocally “Never …”. A year later Herman went on

a business trip to Oslo, sending Aslaug a post card preparing her for business

trips as an excuse for his absence.

Herman

may have understood the impact of the invasion of the Soviet Union in June

1941. Advancing with terrifying speed, German troops conquered vast areas

capturing prisoners of war by hundreds of thousands. Smolensk, the hometown of his

father, fell on July 16. The strategic situation changed. Great Britain was no

longer alone against the Nazi aggressor. The new phase of the war may have confirmed

his earlier decision and helped him solve the dilemma on how to protect his

family. As Herman celebrated his 21st birthday and the coming of

age, his choice was to take responsibility for himself, to be a man of action,

committed to the values of free nations and dedicated to the struggle against

Nazi tyranny.

One

night in August, he left by boat to an island further north, where eight young

men from Stavanger had arranged for a first mate to take them across the North

Sea in an old fishing vessel. Last preparations were carried out in the open

and in the evening people gathered on the quay to bid farewell to the westbound

group. After 58 hours, at sea the group reached Kirkwall on the Orkneys on

August 17. They had to sail the last part as the engine broke down. They were

well received by security officers, representatives of Church of Scotland and

the Norwegian Consulate, offering them clothing, a hot meal, cigarettes and

whiskey. After interrogation by the security officers in Aberdeen, they went by

train to London and the Royal Victoria Patriotic School for final clearance.

Norwegian military authorities took over and within a week, the young men had

their wishes for service granted. Herman joined the air force on September 1,

on the day two years after war in Europe broke out. He was among 10 young

Norwegians selected for an air training camp at Toronto, leaving Liverpool on a

troopship across the Atlantic.

Back home, his father

realised the gravity of the situation. Escaping occupation was an act of

resistance. If arrested for preparing or trying to escape, the German Security

Police would pass a death sentence. Hille went to the local police reporting

his son missing, thus avoiding harassment by the security police and suspicion of complicity in leaving

the country “illegally”.

Herman’s

escape was part of the so-called England-traffic, young people using every kind

of vessel to cross the North Sea in order to report for service in the armed forces

or the Merchant Navy. This traffic lasted from the summer 1940 to spring 1942,

when major losses put an end to it. A top was reached in August 1941 with 40

vessels crossing the sea. In September, over thousand individuals reached the

British Isles. Altogether, 3.300 persons in nearly 300 civilian vessels made it.

Escape was dangerous; one in ten lost their lives.

In

general, considering the small size of the Jewish minority in Norway (about

2.100 in 1940), the part playing an active role during the Second World War was

significant, nearly for percent.

Flying training

The new recruits arrived at Halifax,

Nova Scotia, after a three days voyage. They went by train to Toronto, Ontario,

where the Royal Norwegian Air Force Training Centre, also called “Little

Norway”, had been established in the harbour area near Maple Leaf baseball

stadium. Most of the aspirants entering the camp wanted to be pilots. The

chiefs replied sobering. “For every man in the air we need ten men on the

ground.” After finishing his recruit’s course, Herman had to wait for a flying

course. Through a friend, he sent a letter to Aslaug in Norway via Chicago, thus

avoiding Nazi censorship, informing her in code that he was all right. His

highest wish was to return to her and Stavanger. He had bought himself a violin

and asked her to take care of his parents. This was the only written message he

managed to get through. A Sunday in December, news of the Japanese attack on

the American naval base at Pearl Harbour broke. Once again, the war took a new

turn. It became global. As a fresh air cadet, Herman would hardly grasp the

strategic implications of the attack. Although a stunning tactical success, it

meant a strategic disaster for Japan. The greatest industrial power in the

world had been challenged. United States of America was able to mobilise unprecedented

resources in the battle against the Axis.

Herman

got into the fourth flying course among 31 hopeful. Training involved ground course

with practical and theoretical subjects and elementary flying training school.

His first flying lessons with instructor started April 9, 1942 at Island Airport.

At No. 2 Elementary Flying Training School at Muskoga Airport, where the cadets

learned to fly solo, his problems with landing an aircraft were evident. His

tactile skills applied successfully on the violin did not serve him well at the

yoke. He was excluded – or “washed out” – from the course, to bitter

disappointment. His dream of becoming a pilot was smashed. He got over it,

though. It was no shame being “washed out” – one-half of the aspirants were

rejected as unfit. His talents in navigation however were obvious. He was

transferred to a course for navigators, the first step of the education of

flight navigators. Here he performed with excellence and a course of education,

in accordance with the great Commonwealth Air Training Plan, was laid.

Six Norwegian

aspirants went to a course at No. 6 Air Observer School at Prince Albert. Next,

they attended No. 1 Central Navigation School at Rivers, Manitoba, with over

thousand participants. After a course at No. 7 Bombing and Gunnery School at Paulson,

he earned his navigator/bomb aimer wing and the rank of sergeant. In his leave,

Herman went with friends to New York. The impression of the metropole must have

been overwhelming. He made a concert with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra

at Carnegie Hall his priority. Back at Toronto, the navigators joined their

bomber pilot comrades for a finishing course at No. 1 General Reconnaissance

School RCAF at Summerside, Prince Edward Island, training in coast patrol

duties. Back at “Little Norway”, he served in the camp’s training section.

|

| Herman plays chess with a Britisk offiser, most likely with Vagar on Shetland. Photo:Courtesy Frode Sæland |

In a maritime squadron

Back in Britain, meeting a people still

showing resolve, resilience, restraint and national unity in the war effort gave

inspiration for the new warriors. Herman was detailed to a new, small unit, No.

1477 Flight Royal Norwegian Naval Air Service, Woodhaven, at Dundee, Scotland,

under Coastal Command, operating three Consolidated Catalina flying boats,

doing anti-submarine search, artic patrols and convoy escort in the Battle of

the Atlantic, as well as special duties along the Norwegian coast. He

would have the required flying hours as well as the finishing courses in order

to be an able navigator. He joined an Operational Training Unit course near Enniskillen

in Northern Ireland in May. By July, he was flight navigator, participating in

his first operational sortie as part of Crew

5.

The

rest of 1943, Herman flew anti-submarine search in the patrol area between the

Faroes and Iceland. This was the route used by German U-boats into the

Atlantic. Systematic patrolling by Coastal Command was the most important

preventive measure in securing the Allied convoys across the Atlantic. A sortie

would last from nine to nineteen hours. Usually, the entry in the Operation

Record Book would read; “Nothing observed.” Members of the crews experienced

sorties as futile, as a senseless waste of tiresome flying over desolate

oceans, as boring, strenuous and exhausting routine. During his 18 sorties, Herman

did not see any action at all.

A

career peak would be the special duty tour at Christmas 1943. No. 333 Squadron sent

two Catalinas to the Norwegian coast to boost morale at home. Each aircraft

dropped 50 bags full of scarce commodities like coffee, cigarettes, tobacco,

sugar, candy, fish oil and season greetings from His Majesty King Haakon and

the government in exile. As they flew low-level over islets and sounds on the

coast of Nordland, the crew could see women and children on the ground picking

up the bags. After returning to Woodhaven, a Christmas party was given for the

personnel. Admiral attending opened his speech with the words: “Thoughts go

straight across the North Sea tonight, in both directions.” Herman may have

been silent and thoughtful by these words. He may have thought about his family

at home at the opposite coast. He had not heard from his parents since he left.

An official news bulletin on the persecution of Jews having reached Norway, referring

to the arrest and deportation of Jewish women and children in Oslo, may have

reached him, but no news about families in other parts of the country. I

suppose he was worrying sick about his parents.

In

January 1944, Herman asked for a transfer. He was fed up with routine duties

and wanted to see some action. The request was accepted at once. Although he was

without an advanced flying unit course, he was available immediately in the

pool of RAF personnel.

Published by Scandinavian Jewish Forum

Published by Scandinavian Jewish Forum