|

John Kolstad and Herman Becker on Karl Johan street, Oslo July 1941.

Photo: Courtesy Frode Sæland |

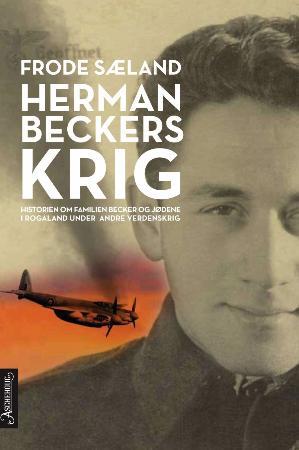

HERMAN HIRSCH BECKER

PART II

by Frode Sæland

Part of Mosquito crew

A Rhodesian with the name Keith d’Alroy Taute, born in 1916 in Fort Victoria, and a veteran pilot in the Royal Air Force, chose Herman as his new navigator. Taute held the rank of Squadron Leader in No. 21 Squadron RAF. He had lost his navigator and needed a new one for The Big Show. Perhaps he saw a young navigator with some experience ready for new challenges. In the RAF, new navigators were usually crewed with experienced pilots.

No. 21 Squadron was one of three squadrons in No. 140 Wing; set up with de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito FB Mk VI. The unit was part of No. 2 Group of Second Tactical Air Force – a force established for tactical air support of the Allied Expeditionary Force under General Eisenhower, preparing for the campaign in North-west Europe. Taute insisted on Herman having officer’s rank and he got his promotion to Sub-Lieutenant in the Royal Norwegian Navy Air Force from June 1, 1944. As he was without AFU and no experience with fast moving aircraft, he was sent to training course at the Group’s Ground Support Unit, a Mosquito Conversion Course as well as temporary flying duties at RAF Station Gravesend, Kent.

The aircrews’ tension increased as preparations for the invasion intensified. On the actual D-day, Keith and Herman trained for firing and bombing runs to be carried out after the landings. On June 7, they got a transfer note for another unit in the wing, No. 464 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force, where Taute would head the “A” flight. The operation order for the wing was to cause maximum delays of all movements by road and railway by enemy forces during night in specific areas beyond the beach heads. On June 9, the Australian squadron received three complete crews, including Taute and Becker, reaching full war establishment. Their first operational sortie on June 10, patrolling roads in Normandy, was unsuccessful, because the four 500 lbs. bombs stuck.

The period from June to October 1944 was a busy one. Depending on the weather conditions, Keith and Herman was on the wings at night, attacking roads, crossing points, railway junctions and marshalling areas with cannon fire, bombs or a combination of both, over places eventually known from the campaign: Cherbourg, Chartres, Mezidon, the Vire-area, the Falaise pocket, the Chagny Rail Yards and Rouen. In October, they carried out their first attacks in Germany, at Saarbrucken. At the end of October, 24 aircraft from the wing carried out a daylight raid against the Gestapo headquarters at Aarhus, Denmark. At the time, Herman enjoyed his long-term leave.

Herman finished a tour of 35 sorties on Mosquito (and over 300 flying hours). The intensity of operative sorties since D-day affected the crews in the form of psychic pressure, mental overload and accumulated unease. The loss of comrades was devastating. Taute left the squadron and Herman was without pilot. Enjoying a well-deserved rest period, his mind was not at peace. During leave in London, an air force colleague told him about recent developments in his hometown. He was informed that his family had been deported to Hitler-Germany. Years of doubt, concern and anxiety turned into certainty. He realised that the Nazis had murdered his family. He must have felt despair and desperation, as well as commitment and will power to go on. Meeting an acquaintance from Stavanger, offering him a rest period in Canada, he declined with the words: “I am going to get those bastards.”

Herman knew it was difficult to shun an obligatory rest period. Norwegian authorities declined his first request. However, he knew whom he had to speak to in order to get a new operational tour. Probably, he talked with the personnel officer of No. 140 Wing, who conferred with Wing Commander Bill Langdon of 464 Squadron. He met with Langdon, who granted him a second tour without any formality. A couple of days later Squadron Commander Langdon wrote a recommendation for the award Distinguished Flying Cross: “This Officer possesses a very high standard of Navigational ability which he employs to the utmost in his duties. His efforts have been a fine example of skill and devotion to duty. He has elected to return to this squadron for his second Operational tour and he will undoubtedly play an outstanding part in future operations carried out.”

King George V sanctioned the DFC for Sub-Lieutenant Herman Hirsch Becker in January 1945, and he could fix his first ribbon, alternating violet and white diagonal stripes, above the left breast pocket of his battle dress. The same month, the Norwegian Ministry of Defence followed suit by recommending him for The War Medal, number four of military awards for service during Second World War. He could add a ribbon with stripes of gold on red, the colours of the national banner.

Herman Becker, in the middle, during the Wings Parade in "Little Norway"

Photo: Courtesy Frode Sæland

As Herman started his second tour in November 1944, No.140 Wing was attacking communication targets in the Netherlands. He eventually crewed with an Australian, Flying Officer John Herbert Palmer. In December, their area of operations moved southwards to Luxembourg - Koblenz, due to the Ardennes Offensive. On Christmas Eve, their mission was to bomb German munitions transports in the Ardennes salient, in support of Patton’s III Corps, struggling to break through to Bastogne from the south against heavy resistance. After the turning point of the Battle of the Bulge, as the headquarters of Hodges’s First Army and Simpson’s Ninth Army celebrated New Year’s Eve with turkey and champagne, 18 fighter-bombers from Herman’s squadron attacked village and railway targets at the northern front, under atrocious weather conditions.

In February, the wing relocated to a provisional airfield at Rosières-en-Santerre south of Amiens. The squadrons were immediately involved in the launch of Operation Veritable, preparing for the crossing of the Rhine. The first sortie for Herman and John was bombing and strafing the usual targets in direct support of the Canadian First Army at the northern end of the front. At the end of the month, they participated in a massive large-scale daylight attack on communications network targets in the area Bremen – Hannover, as part of Operation Clarion.

Herman was the only Norwegian in an Australian squadron, consisting of mostly Australians, Britons, Canadians and New Zealanders – a typical Commonwealth unit. He distinguished himself by carrying his navy blue uniform with pride. How did he fit in? Some say he fitted in very well; he was well regarded and highly respected for his skills. Some say he was a quiet, self-contained person, who did not get close to anyone – a lone wolf. Some say he was “an absolutely delightful person”, first class, with a warm personality. All relevant aspects of what I would call an ordinary person, not extraordinarily ordinary, but a usual chap and a good bloke – admittedly of the quiet, sensitive and introvert kind. I suppose none of his brothers in arms had any idea of the anguish, pain and black sorrow he carried within him. However, he would be welcome in a unit where skill, competence and sense of duty were central criteria, where an egalitarian Aussie attitude ruled and where racial prejudice played no part.

In March, as the Battle for the Rhine raged on the ground, they flew Intruder operations as usual ahead of the front. As frequency dropped, the crews had time to practice on pinpoint raids, specialised low-level daylight attacks on selected targets, for which No. 140 Wing became renowned. At the end of the month, the secret mission to attack the Gestapo Headquarters in Copenhagen was authorised. The next morning, seven Mosquitos of 464 Squadron took off for an airfield at Fersfield, East Anglia, to conduct the raid.

First Pilot 5247 Herman H. Becker

Photo: Courtesy Frode Sæland

Operation Carthage

The Danish Resistance had requested an attack on the Gestapo HQ via Special Operations Executive (SOE) in London in order to gain some respite, to stop the break-up of resistance cells and free central cadres incarcerated at the top floor of the Shell building, in order to prepare for the Liberation. The briefing of the crews reflected the meticulous planning of the raid. They were shown photos, specially designed slides, film footage, and charts with flak positions marked, a system of fix points, specially designed models and several types of maps. All in order to carry out a surprise attack, to bomb only the lower floors of the office building situated in a densely populated area, and to avoid added flak capacity of a newly harboured German cruiser. The briefing was repeated thrice. After the briefing, Herman met the Danish SOE representative Major Truelsen in the officers’ mess, giving him photographs of his family in Norway, asking him to keep them safe for him. I see this as an expression of a fatalism typical of experienced warriors and Herman’s wish to leave a personal sign to his neighbours.

In the morning, March 21, 1945 18 Mosquito fighter-bombers from No. 140 Wing took off in three waves of six aircraft in clear but windy weather. 31 North American P-51 Mustang fighters from Fighter Command escorted the attack force. A two hours bumpy crossing of the North Sea at very low-level covered the windscreens with salt spray, reducing visibility. The first wave reached a gloomy Copenhagen on time, increasing speed to 300 mph. In the final run-in, the fourth aircraft hit a light tower, got out of course and crashed at some garages along a city boulevard, catching fire almost immediately as the ammunition exploded. The three first aircraft bombed the target building, the fifth hit as well, while the last missed due to an evasive manoeuvre.

The second wave arrived over a minute later and black smoke from the fire made navigation difficult. The two first crews could not see the target and decided to do another turn; the first bombed the Shell house, while the other decided to bring their bombs back. The third aircraft got out of course, lost a bomb and sent the remaining bomb against the fire, hitting the Jeanne d’Arc convent school nearby. The crew in the fourth aircraft observed the confusion, made a turn and came behind the fifth (Palmer & Becker) and the sixth aircraft. They were both on course but a tiny distraction made them bomb a nearby building complex. The last aircraft hit a pillbox on the corner of the Shell house.

Herman in full uniform onboard Catalina aircraft that was involved

in almost every major operation in World War II

Photo: Courtesy Frode Sæland

The third wave arrived somewhat late due to navigational problems. On a northerly course, they were led directly to the roaring inferno of the crash. Smoke obscured final fix points and most of the crews mistook the smoke for the target. Five of the six aircraft released their bombs in the Frederiksberg area, as well as the last Film Production Unit Mosquito with incendiary bombs. The sixth aircraft realised the mistake and brought the bombs back.

The attack took about five minutes and the raiders set course for home, flying at low-level in small groups across Sealand. Five aircraft of the first wave made it to East Anglia after a five and a half hours trip. The two last aircraft of the second wave came too far north and were his by flak as they left the coastline. Palmer and Becker saw the sixth aircraft turn north and crash in the sea. Palmer tried to keep his aircraft steady with one engine, turning off the other engine to reduce the fire. After a distance, the aircraft crashed in the sea in flames. Herman opened the emergency hatch and got out on the fuselage, which was pulled down by the rough sea. The tailfin must have hit him on the head as the aircraft sank into the sea. Knocked unconscious, he drowned in the Samsoe belt. Alone. Thus Herman fell.

Herman Becker August 1944

Photo: Courtesy Frode Sæland

Epilogue

At the base at Rosières-en-Senterre, France, the keeper of 464 Squadron’s Operation Record Book had difficulties in accepting the loss of veteran crews in the day’s raid, after receiving news from Fersfield in the evening. “Unfortunately, the day’s work has cost us four well tried veterans – F/O “Spike” Palmer and his Norwegian Navigator – S/Lt. Herman Becker, also F/O “Shorty” Dawson and his Navigator F/O “Fergie” Murray. All these chaps had been long with the Squadron and their loss is not only a shock to us all but a severe blow to the Squadron. There is a slight hope that they have “ditched” and got away – such is our hope.” Officially, the crews were missing in action. The keeper of the Operations Record Book of No. 2 Group, however, had no illusions, regardless of reports of Herman waving farewell as the aircraft ditched and a crewmember observed at the fuselage. A later entry stated shortly that Herman was “killed”. Presumably, he got a wet grave just like his pilot.

Four days later a corpse was washed ashore on the island of Samsoe, east of Jutland. Local fishermen found nothing to identify the dead, but from the Navy battle dress, they assumed he was a British airman. They handed the corpse over to German authorities, who buried the corpse in secrecy at Tranebjerg cemetery, in order to avoid manifestations by the local population.

After exhumation in 1947, British authorities decided that the remains belonged to a British officer from Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. Identification showed the rank of Sub-Lieutenant, an unknown pilot wing with the letter ‘S’ on a red circle, two ribbons, one of an unknown award, the other of DFC, and a small kangaroo emblem inscribed “Australia”. A simple headstone read “Unknown British Flyer”.

In the 1990s, Colonel Helge William Gram of the Danish Army pioneered an identification project of the 1.100 aviators from the Commonwealth countries and the USA that lie buried in Denmark. After eight years of work, 90 were still unidentified. Trying to identify an Allied pilot, Mr. Gram received a copy of the 1947 exhumation report at Samsoe that puzzled him. In 1994, a request originating from Mr. Gram started my quest for a family history. A reinterpretation identified the unknown pilot at Samsoe as Herman Hirsch Becker. Gold wing with an ‘S’ in centre was definitely a Norwegian navigator wing (S for speider). In consultation with Norwegian authorities, The Commonwealth War Graves Commission accepted the identification in the year 2000. The same year, a new head stone with his name was erected. In 2010, the Star of David was engraved on the stone. Finally, his grave got a name and a broader audience has to know of his war efforts.

Published by

Scandinavian Jewish Forum