|

| Abraham Baer (1834 - 1894) |

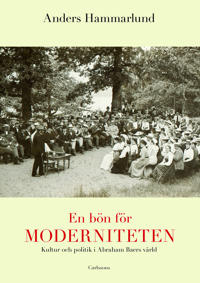

A PRAYER FOR MODERNITY

POLITICS AND CULTURE

IN THE WORLD OF

ABRAHAM BAER

ABRAHAM BAER

Summary by Anders Hammarlund

My book A Prayer for Modernity (En bön för moderniteten : kultur och politik i Abraham Baers värld) deals with the interaction between two reform movements in Europe during the 1800's – the Swedish and the Jewish. In 1857, a young Abraham Baer took the position as cantor of the newly founded synagogue in Gothenburg.

Twenty years later, he produced one of the century’s most remarkable Swedish publications, a handbook of Jewish liturgical music, Baal t’fillah oder der practische Vorbeter. This work is considered a milestone in Jewish cultural history–it is the most ambitious documentation of European synagogical music that was undertaken during the 1800s.

Born and raised in the German-Polish borderland, Baer was greatly influenced by the stormy love-encounter between Jewish learning and modern science, a relationship whose offspring was named Kulturwissenschaft, nurtured in Berlin’s intellectual greenhouse.

In Jewish Gothenburg, which became a virtual cultural suburb of Berlin, Abraham Baer met Swedish radicals who were striving to dismantle ståndssamhället – the strongly regulated, feudal segmented society–in order to replace it with a modern nation-state. Their faith in progress, education, and freedom was limitless. They wanted to embrace modernity, while still revering tradition.

But what is a nation, and what is the basis for belonging? What unites these liberated citizens in an emancipated society, where religion becomes solely private, and not a matter for the state? Can religious worship be rationalized? What makes society possible?

When Abraham Baer arrived in Gothenburg to start his appointment as cantor and shochet, he immediately became embroiled in the lively discussions about the modernization of synagogal worship. The board of the congregation was dominated by eager reformists, who took their models from contemporary striving in Berlin, Breslau and Hamburg.

Some of them even advocated the abandonment of Hebrew as the liturgical language. Their musical concepts were strongly informed with the universal ideals of German art music. It was clear that they wanted a new and ”modern” music for the new synagogue, but the exact content and meaning of this ”modernism” was hard to define.

Some of them even advocated the abandonment of Hebrew as the liturgical language. Their musical concepts were strongly informed with the universal ideals of German art music. It was clear that they wanted a new and ”modern” music for the new synagogue, but the exact content and meaning of this ”modernism” was hard to define.

This aesthetic infighting in the congregation was accompanied by an increasing influx of immigrants from eastern Europe. These, who were often Yiddish-speakers with a traditional Jewish world view, felt estranged by the modernizing changes in music and worship. Abraham Baer seems to have taken the role of a mediator between these opposing factions in the congregation.

”Contemporary art music certainly is wonderful and a beacon of progress; however, we should realize that we have a rich and specifically Jewish music as well, an oral tradition that we must not forget to cultivate in its own right” he tried to say. This is in a way the central message of his Baal t’fillah.

Baer’s work with the publication was in an interesting way supported by some of Gothenburg’s non-Jewish intellectuals, like journalist and politician S. A. Hedlund, who was Sweden’s leading liberal molder of public opinion and editor-in-chief of Handelstidningen, the trend-setting Gothenburg daily of the period.

Therefore, in order to analyze the cultural setting that produced the Baal t’fillah oder der practische Vobeter, I have painted a colorful fresco of Gothenburg’s 19th-century Jewish and non-Jewish lebenswelt.

Meet rabbi Moritz Wolff, the accomplished Maimonides scholar; Prague-born Christian composer Joseph Czapek, organist of the synagogue; professor Karl Warburg, founder of modern Swedish literary studies and chairman of the Jewish congregation; journalist and indefatigable social networker Mauritz Rubenson; photographer, badchen and stand-up comedian Aron Jonason; and philanthropist and sloyd educator Otto Salomon. They were all deeply engaged in a prayer for modernity.

Meet rabbi Moritz Wolff, the accomplished Maimonides scholar; Prague-born Christian composer Joseph Czapek, organist of the synagogue; professor Karl Warburg, founder of modern Swedish literary studies and chairman of the Jewish congregation; journalist and indefatigable social networker Mauritz Rubenson; photographer, badchen and stand-up comedian Aron Jonason; and philanthropist and sloyd educator Otto Salomon. They were all deeply engaged in a prayer for modernity.

Abraham Baer was born in Wielen, Poland. He worked as a cantor and teacher in several communities throughout western Prussia before settling as a cantor at the Goteborg Synagogue in Sweden in 1857.

During his tenure there, along with organist Joseph Czapek, he published Musik till sangerna vid Gudstjensten (1872), a two volume collection of hymns made up primarily of Salomon Sulzer’s liturgical compositions and arrangements.

In 1877 Baer finished his most noted work, Baal Tfilla, a collection of over 1,500 melodies from the Polish, German and Sephardi rites. Baal Tfilla includes original compositions, as well as music borrowed from Salomon Sulzer, Louis Lewandowski and Samuel Naumburg, covering the liturgy of the entire Jewish calendar year.

For further reading, see link here.

For further reading, see link here.